The Science of Reading Isn’t Complete Without Writing

Writing Strengthens the Upper Strands of the Reading Rope

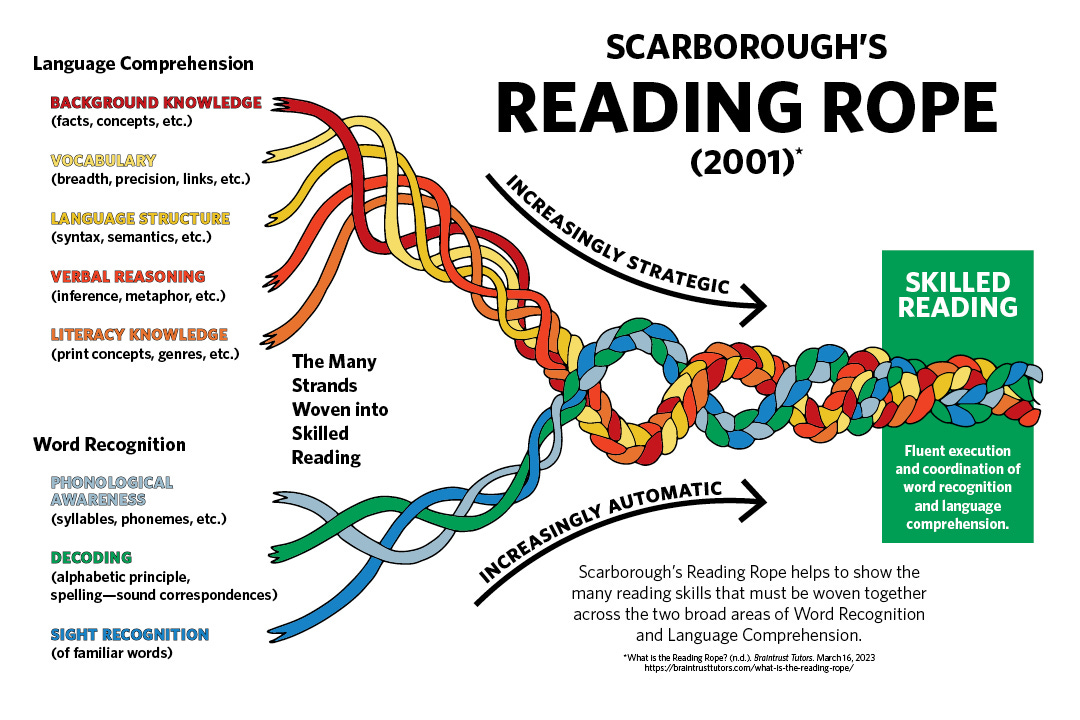

The Science of Reading (SoR) movement has brought a lot of much-needed clarity to early literacy instruction, correcting past imbalances by emphasizing systematic phonics, phonemic awareness, and decoding. This focus on word recognition (the “lower strands” of Scarborough’s Reading Rope) has led to measurable gains in decoding fluency and foundational reading skills for many students.

But as SoR becomes embedded in state policies, district mandates, and commercial curricula, a critical problem has emerged: many SoR-aligned programs offer no meaningful solution for writing instruction. They prioritize decoding while neglecting the essential “upper strands” of the Reading Rope—vocabulary, syntax, background knowledge, and verbal reasoning—all of which are closely tied to writing.

As a result, students may learn to sound out words with increasing fluency, but lack the tools to think deeply, express themselves clearly, or comprehend complex texts.

The Upper Strands: Often Overlooked, Always Essential

Scarborough’s Reading Rope provides a widely accepted model of skilled reading, composed of two interdependent domains:

Word Recognition: phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition

Language Comprehension: background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and comprehension strategies

While decoding becomes increasingly automatic with instruction and practice, language comprehension must become increasingly strategic. The upper strands are not ancillary – they are essential to comprehension. Students cannot become proficient readers without robust language comprehension skills.

Yet many SoR-aligned programs devote the majority of instructional time to the lower strands, especially in grades K–2, leaving limited space for knowledge-building, deep vocabulary work, or extended writing. This imbalance risks producing students who can sound out words fluently but struggle to make meaning from complex texts.

Reading and Writing: A Reciprocal Relationship

A growing body of research highlights the deep cognitive and developmental connections between reading and writing. Far from being isolated skills, they are mutually reinforcing processes that draw on shared knowledge and strategies:

Both rely on understanding text structures, syntax, and vocabulary.

Both require background knowledge and the ability to organize ideas.

Both benefit from explicit instruction and frequent opportunities for practice.

As literacy expert Timothy Shanahan explains, reading and writing share “a lot of real estate”: phonological knowledge, vocabulary, grammar, text structure, and reasoning all contribute to success in both domains.

Recent analyses by Steve Graham and colleagues reinforce this point. Studies show that:

Teaching writing improves reading comprehension and fluency.

Teaching reading improves writing quality and structure.

Integrated instruction in both yields stronger results than isolated instruction in either.

Writing is not just an output skill – it is a powerful tool for reinforcing and internalizing reading strategies.

Writing Supports Vocabulary and Syntax

Vocabulary is a key component of language comprehension. Yet many skills-focused reading programs provide only superficial exposure to new words. Writing provides a meaningful solution: writing requires students to use vocabulary actively, applying new terms in original sentences, summaries, or analyses. This kind of active processing promotes deeper word knowledge and long-term retention.

Similarly, writing sharpens students’ awareness of sentence structure and grammar. While reading can expose students to sophisticated syntax, writing requires them to produce it. Constructing complex sentences, mimicking literary styles, or experimenting with figurative language deepens students’ understanding of language forms. This reinforces the very same upper-strand skills educators seek to build through reading instruction.

Writing Builds Background Knowledge

Background knowledge is a key predictor of reading comprehension. Numerous studies, including those by E.D. Hirsch and others, have shown that readers with greater domain knowledge comprehend texts more easily, particularly in content-rich subjects like science and history.

Writing supports the development of background knowledge by encouraging organization, synthesis, and explanation of new content. When students write about what they learn – summarizing a science article, explaining a historical cause-and-effect relationship, or describing an experiment – they not only deepen their understanding, but they are more likely to remember and retrieve that knowledge later.

Meta-analyses (e.g., Graham et al., 2020) have confirmed that writing-to-learn activities improve content acquisition in science, social studies, and math. These effects are especially strong when writing is closely tied to reading and inquiry, and when students are asked to explain, analyze, or reflect on what they’ve read.

Writing Improves Comprehension

Writing is not just a tool for reinforcing reading—it is a direct means of improving comprehension. Asking students to write about a text, whether through summarizing, responding to prompts, or analyzing character motivations, helps them clarify meaning, identify key ideas, and monitor their understanding.

Graham and Hebert’s (2011) review of over 100 studies found that students who wrote about texts (through written answers, summaries, or notes) demonstrated significantly greater reading comprehension than peers who did not.

This writing-about-reading approach is particularly valuable for:

Students who struggle with inference or synthesis

English learners developing academic language

Any student encountering complex or content-rich texts

Even brief writing exercises, such as quick-writes, exit tickets, or two-sentence summaries, can make comprehension visible and offer teachers powerful formative data.

Integration Is Key

Perhaps the most important takeaway from recent research is this: reading and writing should be taught together, not in silos.

A 2017 meta-analysis of balanced literacy programs found that instructional approaches which integrated reading and writing instruction (rather than favoring one) produced the most consistent gains across both domains.

Integrated practices include:

Reading a text and writing a response (summary, opinion, explanation)

Teaching comprehension strategies through both reading and writing tasks

Using writing to build vocabulary and reinforce background knowledge

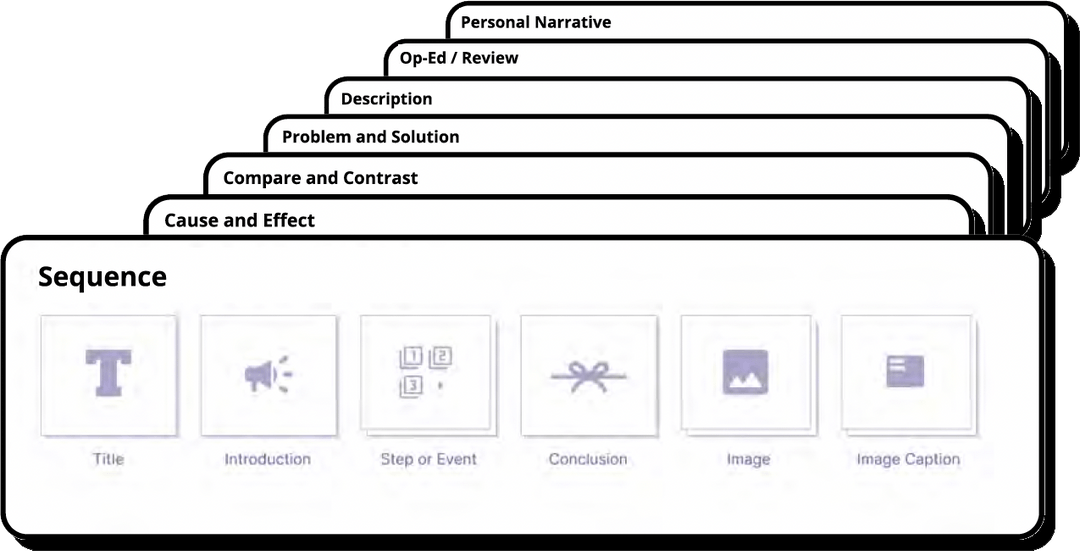

Explicit instruction in text structures used for both reading and writing (narrative, expository, argumentative)

Such integration helps students see the purpose and relevance of both skills—and allows the upper strands of the reading rope to grow in strength alongside decoding fluency.

Implications for Practice

To fully realize the promise of the Science of Reading, educators and curriculum designers must re-center writing within early and ongoing literacy instruction. This doesn’t mean reducing decoding time or delaying phonics – it means ensuring that comprehension, vocabulary, syntax, and content knowledge are addressed in tandem, with writing as a central vehicle.

Key shifts might include:

Embedding writing tasks into every major reading activity

Prioritizing writing-to-learn in content areas (science, history)

Teaching sentence construction and grammar explicitly

Modeling how writing mirrors the structure and logic of texts

Creating time for extended writing aligned with reading goals

As schools refine their SoR-aligned practices, it’s essential to move beyond the lower strands of the rope. Writing is one of the most powerful tools we have to develop the upper strands – vocabulary, language comprehension, and knowledge-building – that make reading truly meaningful.

By integrating writing into the fabric of literacy instruction, we can help students become not just fluent decoders, but thoughtful, expressive, and confident readers and writers.

References

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy Research (Vol. 1).

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2011). Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review

Graham, S., Liu, X., Aitken, A., Ng, C., Bartlett, B., Harris, K., & Holzapfel, J. (2017). Effectiveness of literacy programs balancing reading and writing instruction: A meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly,

Graham, S. (2020). The sciences of reading and writing must become more fully integrated. Reading Research Quarterly

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S., & MacKay, M. (2020). The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research

Shanahan, T. (2016). Relationships between reading and writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of Writing Research

Shanahan, T. (2020, September 18). What is the Science of Reading? Shanahan on Literacy

Sawchuk, S. (2023, January 17). How does writing fit into the ‘Science of Reading’? Education Week.

Sedita, J. (2024, May 31). Connecting the ropes: Integrating reading & writing instruction. Keys to Literacy

Hansen, L. (2024, July 9). Why it’s so important to have students write about what they read.